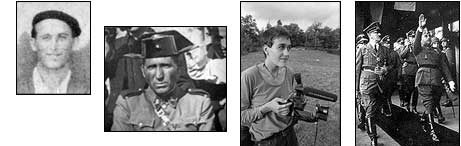

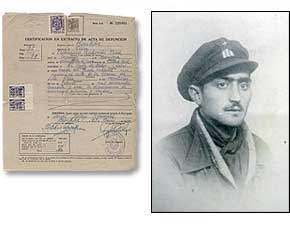

On February 26th, 1948, my grandfather, Francisco Redondo, died while in the custody of Spain’s Civil Guard. His autopsy report says he died from a brain and pulmonary hemorrhage. The police report said he was “legally” shot while trying to escape. Everyone else says he was murdered.

My grandfather was a casualty of Spain’s secret war – a guerrilla campaign fought against the Franco regime from 1939 to 1951. It was a war hidden from the rest of the world and it was fought most fiercely in the mountains of Northern Spain, where my grandparents lived. Francisco had been persuaded by friends to hide a group of guerrillas who were trying to escape to France. But someone gave them away and on the night of February 21st, the local Civil Guard surrounded my grandparent’s house and ordered the men to surrender. When they didn’t come out, the Civil Guard burned the house down. The guerrillas escaped, but my grandparents were arrested and taken to jail. After five days of interrogation, Francisco, was taken to a hill above the village and shot. My grandfather was just 35 years old and left behind a widow with four young children. My grandmother, Josefa Martinez, was sentenced to two years in prison. Both her and my grandfather’s family, would help care for the children until she was released. Years later, I returned to El Valle, my family’s home in Spain, to find out for myself why my grandfather had been killed. My family, however, refused to discuss my grandfather. They said I would never find out the truth and that I was just stirring up trouble with all my questions. My great-grandmother, who buried Francisco, now claimed not to know how he had been killed. Even my uncle, who at first seemed keen to help, became angry when I tried to interview him. In the government archives, I found the autopsy report that described how Francisco was shot ten times. I managed to find old guerrillas, including one who had actually stayed with my grandparents. He told me of the “Law of Escape” – the Civil Guard would tell prisoners they were free to go, and then shoot them as they tried to run away. In this way, they could “legally” justify the execution of so many without having to ever hold a tribunal. As I continued investigating, the people of El Valle seemed to grow more and more uncomfortable with me.

Villagers who had promised to help me one day, acted like they didn’t know me the next. But that didn’t stop some from talking. Through whispers and sneers, it became obvious that the old hatred was still very much alive, and that the whole village blamed two of my grandmother’s cousins for Francisco’s death – Donato and Rosario. Donato had died a few years ago and Rosario no longer lived in Spain. The only thing left to do was to try and find her. Then I stumbled on an official case file that named the guards who’d shot my grandfather. One of them was still alive. I had no choice but to go and confront him.